Nathan vs. the World

Nathan Wells and I work together in the same office. For several months, Nathan has had a chess board sitting on his desk, where he invites anyone visiting his office to make a move for the “office team’. He started this little social experiment to see how well the visitors, acting in some ways a an independent actors, could compete against himself, who had the benefit of managing long-term strategies through continuously playing one side. The answer is, not surprisingly, not very well. Nathan beats the “office team’ fairly consistently. There are a few reasons for this:

- His opponents can’t mount a larger strategy because no one is sure if the next person will see the plan.

- Some of those on the “office team’ really aren’t chess players, and tend to make moves that are either unhelpful, or at times, detrimental.

- Other players can’t undo these bad moves, as the structure basically allows anyone who wants to elect themselves as “dictator for the moment’.

- Nathan always has access to the board and can muse over the moves over time, while his opponent usually only has a minute or two to make a decision.

Nathan and I had talked about this a number of times and how it applies to leadership and group dynamics. I must also admit a bit of grousing on my part that I seemed to only get involved in the game once it was beyond all hope–my office isn’t particularly near Nathan’s. Let’s just say there were a few times I forfeited for the “office team’ when there was no way to avoid an inevitable check-mate.

Through these discussions, we came to better understand how the structure of the game was creating the

dynamics we were seeing. So, we decided to try building a different structure to see if it would change the

game dynamics. Enter Amazon‘s Mechanical Turk. I mentioned Mechanical Turk in my article “Why the worry? I’d rather wonder.’ Basically, it allows

one to put up a task for people to do, assign a price to it, and get back results. Using this approach,

we should be able to crowd-source a chess game. We decided to do that… pit Nathan against the entire

world (well… against people from the entire world.

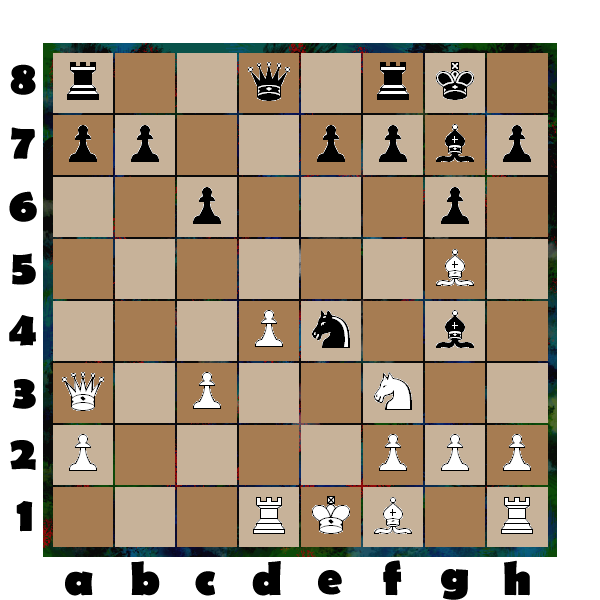

Before diving deep into it, there needed to be a test. I decided on a board from the celebrated “Game of the Century’ in 1956 between Donald Byrne and then 13-year-old Bobby Fischer. The chosen board is from partway through the game just slightly past the point where Byrne made the slip that eventually cost him the game. It’s white’s move. The idea was to post this board to Mechanical Turk with instructions to provide what was thought to be the best move. We’d take fifty valid responses (i.e., valid moves) and treat each one as a vote. Whichever user-provided move received the most votes would be the one that was chosen for the “world team’. As we expected a wide range of responses of varying sophisitication, we wanted to see if the “world team’ would chose the same move as the Chess Grand Master. Here are the results:

| g5⇀e7 | ||

| h2⇀h3 | ||

| f1⇀d3 |

|

|

| a3⇀e7 | ||

| f1⇀e2 | ||

| a3⇀a5 | ||

| f1⇀c4 | ||

| a3⇀a6 | ||

| a3⇀b3 | ||

| a3⇀b4 | ||

| a3⇀c1 | ||

| d1⇀b1 | ||

| d1⇀c1 | ||

| d1⇀d3 | ||

| f3⇀d2 | ||

| f3⇀e5 | ||

| f3⇀h4 | ||

| g5⇀e3 | ||

| g5⇀h4 | ||

In the original game, Byrne decided to go with g5⇀e7. Our “world team’ had chosen the same. Good–a rational choice.

| Country | Participants |

|---|---|

| India | |

| United States | |

| Romania | |

| Italy | |

| Taiwan | |

| Venezuela | |

| Vietnam | |

| Unknown |

Now on to the real games. Can Nathan win out against a crowd-sourced opponent. We suspect so, though think it will likely be more difficult than his bouts against the “office team’. The “world team’ still has these disadvantages:

- The team isn’t going to be the same set of people each turn.

- It’s effectively play-by-committee.

- Team members can’t easily communicate one with another, avoiding group think, but also coordination. Consequently, long-term strategies will likely be difficult.

Nathan and I both suspect the result will be a mediocre player, as the voting system will not only remove the bad moves, but also the subtle, brilliant ones. Only the games will tell.